2025 marked the widespread adoption of coding agents — harnesses that autonomously write, test, and debug changes to software with minimal human intervention. Products like Claude Code, Codex, Cursor, and Open Code are churning out unfathomable lines of code a day. A recent large-scale study of GitHub repositories estimated that 16 to 23 percent of code contributions already involve such tools, within months of their becoming widely available.

The speed of the shift has caught even experienced practitioners off guard. In late 2025, Andrej Karpathy described going from 80 percent manual coding in November to 80 percent agent-assisted coding in December — a complete inversion of his workflow in weeks. He called it the biggest change to his coding practice in two decades, noting that the intelligence suddenly felt ahead of the infrastructure needed to support it.

A few random notes from claude coding quite a bit last few weeks.

Coding workflow. Given the latest lift in LLM coding capability, like many others I rapidly went from about 80% manual+autocomplete coding and 20% agents in November to 80% agent coding and 20% edits+touchups in…

— Andrej Karpathy (@karpathy) January 26, 2026

The gap between what coding agents can now do and what they need to do reliably over long, complex tasks is the central problem. And it is compounded by a simultaneous second shift in the rise of agentic applications.

Two Shifts at Once

The applications these agents are building have changed, too. Modern software increasingly blends traditional code with LLMs and natural language prompts. A customer support application might use conventional code for its API layer, a fine-tuned model for intent classification, and a prompt-driven agent for resolution. The behavior of that system is not fully specified in any single artifact. It emerges from the interaction of code, weights, and prompts — and it varies at runtime in ways that deterministic software never has.

Karpathy anticipated this trajectory years ago when he described neural networks as a fundamentally different way of writing software — the “code” being learned weights rather than hand-authored logic.

By 2025, he had extended the framework to natural language prompts as a third paradigm: “Your prompts are now programs that program the LLM.”

So agents are writing code for systems whose behavior is itself partially defined by models and prompts. Traditional software engineering practices were designed for a world where humans wrote deterministic code. Neither assumption holds anymore. We now need infrastructure that addresses both sides of the equation — the new authors and the new kind of software they produce.

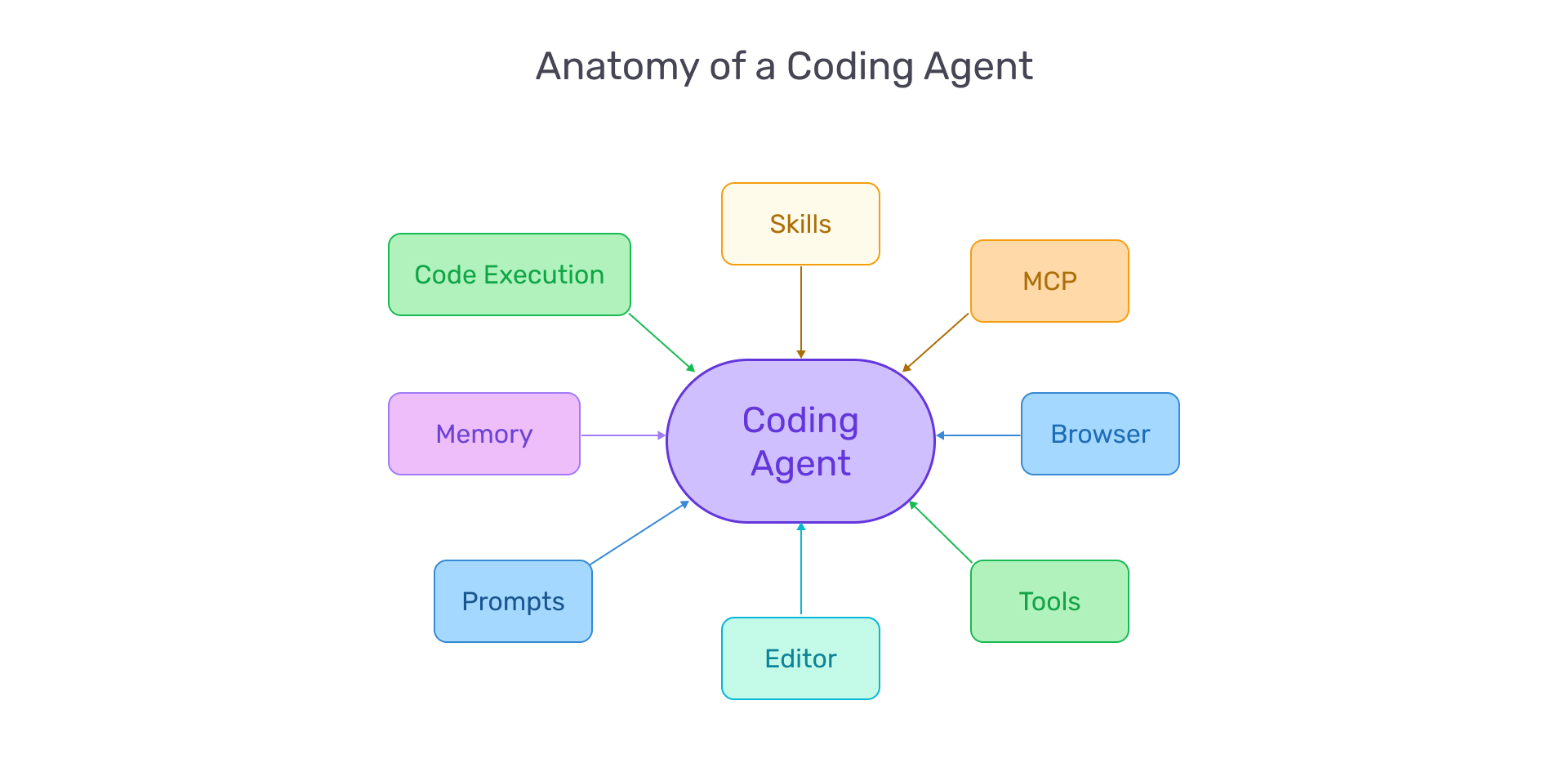

The Agent Is Not Just a Model

A coding agent is more than a large language model. What makes these systems functional is what practitioners call the agent harness: the infrastructure that wraps around the model and governs how it operates. The harness manages the loop of processing inputs, orchestrating tool calls, maintaining context across turns, and returning results. It handles everything the model cannot do on its own — filesystem access, environment isolation, permission controls, and the feedback mechanisms that allow the agent to verify its work.

The distinction matters because improving an agent’s reliability is less about improving the model and more about improving the harness. As Anthropic’s engineering team has documented, even a frontier model running in a bare loop will fall short of production-quality software given only a high-level prompt. Without structure, the model tries to do too much at once, loses track of state, and lacks the feedback needed to self-correct. The harness imposes discipline: breaking work into incremental steps, persisting progress, and providing verification checkpoints.

Two requirements follow. First, agents need tooling access — documentation, telemetry, debugging tools, and system context comparable to what human developers rely on. Second, they need embedded best practices. Techniques like tracing and evaluation are evolving rapidly, and agents must be equipped with them from the outset rather than waiting for human reviewers to catch mistakes after the fact.

The Case for Telemetry

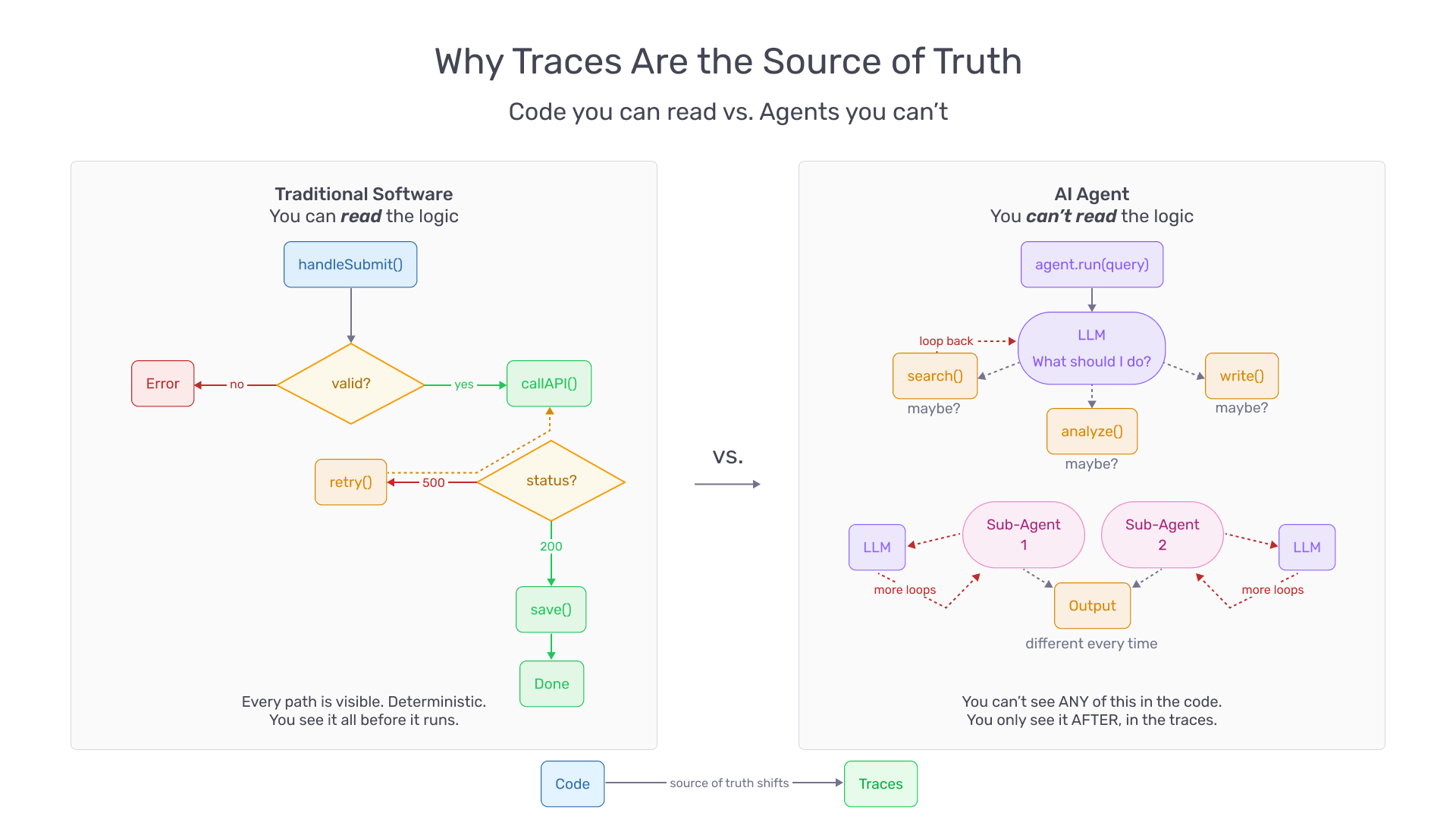

In traditional software, you read the source code to understand what the application does. The decision logic is deterministic, inspectable, reviewable. In agent-driven applications, the code is scaffolding. It defines which model to call, which tools are available, and what instructions to provide. The actual decision-making — which tool to invoke, how to reason through a problem, when to retry — happens inside the model at runtime.

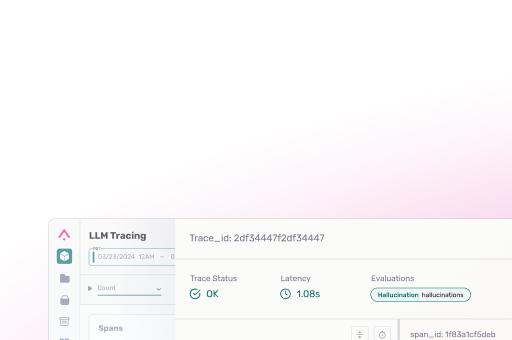

As LangChain founder Harrison Chase put it: in software, the code documents the app; in AI, the traces do.

Traces capture how an agent behaves in practice — how many times it loops, which tools it invokes, where in the topology failures emerge. They are the source of truth for what an agentic application actually does, as opposed to what the code says it should do. Every operation developers traditionally performed on code — debugging, testing, optimizing, monitoring — must now be performed on traces.

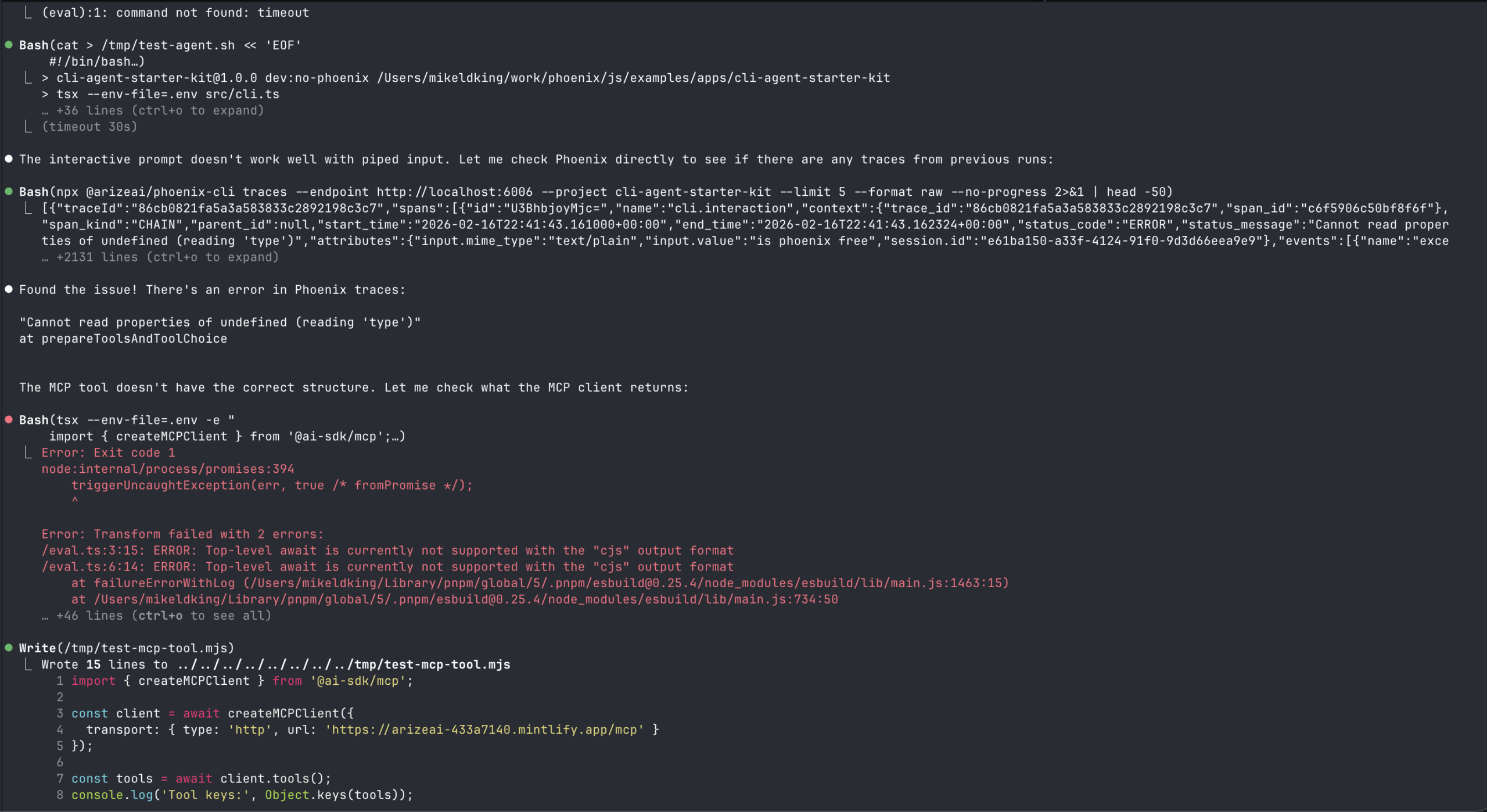

The implications for coding agents are direct. A coding agent without trace access is an agent working without documentation. It will guess where failures occur, propose changes based on incomplete information, and generate the review overhead that automation was supposed to eliminate.

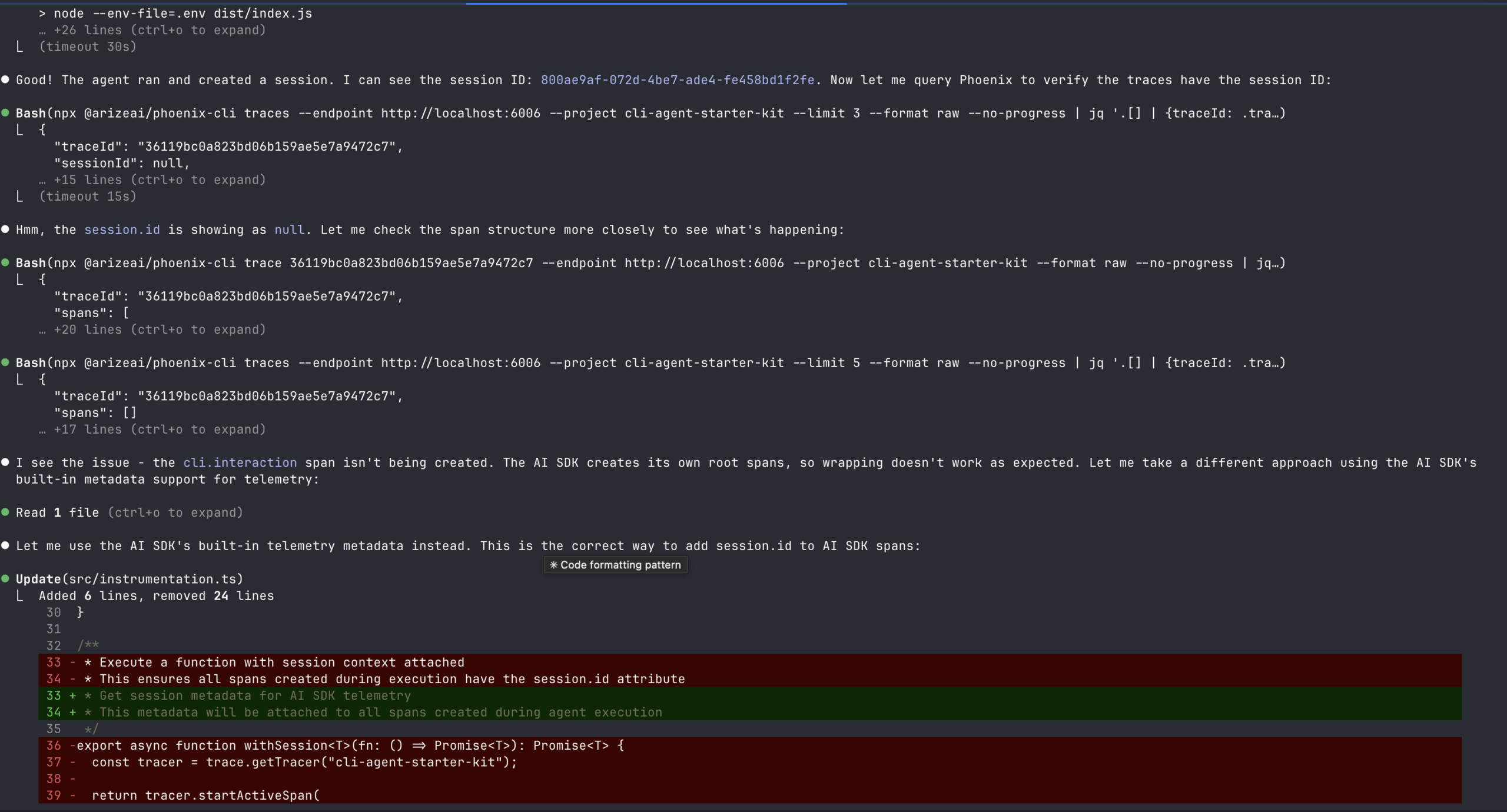

A coding agent that can query traces sees what actually happened at runtime. It can identify reasoning errors, detect tool call loops, correlate prompt changes with behavioral shifts, and validate that its modifications produce measurable improvements. Without that access, the self-improvement loop breaks at its most critical point: verification.

What Full Autonomy Could Look Like

These concerns become urgent as coding agents approach genuine autonomy. OpenAI recently documented the experience of building an internal product entirely with Codex agents — approximately one million lines of code across 1,500 pull requests, with zero manually written code (see: harness engineering). The project revealed what happens when engineering shifts from writing code to designing environments, specifying intent, and building feedback loops.

Early progress was slower than expected — not because the agents were incapable, but because the environment was underspecified. When something failed, the fix was almost never “try harder.” Instead, engineers asked: what capability is missing, and how do we make it legible to the agent?

Two findings stand out.

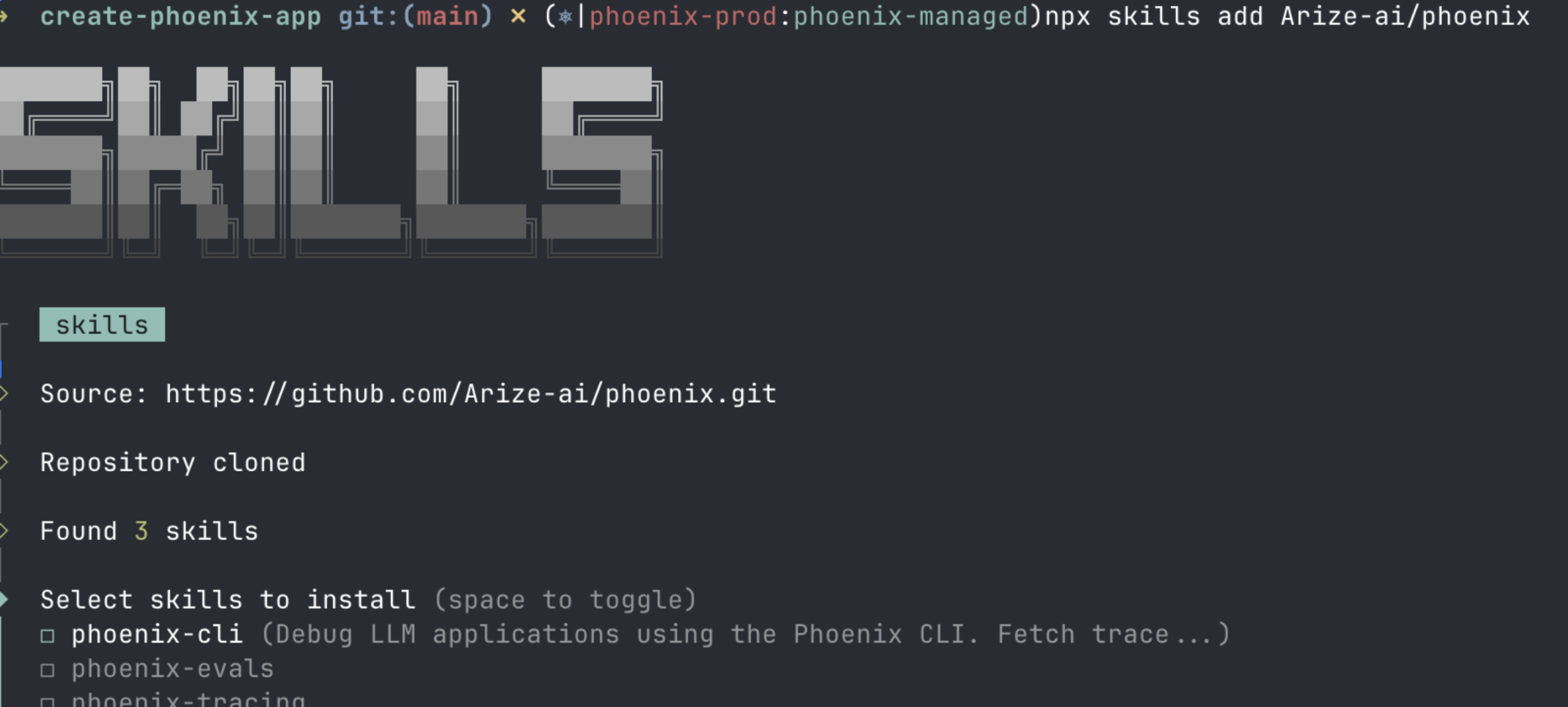

The first was that dumping context into a monolithic instruction file fails predictably. Large instruction documents crowd out the task at hand and decay as the codebase evolves. What worked was treating knowledge as a structured system of record — a map, not an encyclopedia — with pointers to deeper sources of truth. In the language of agent development, these are “skills:” focused, composable units that encode not just what tools to use, but when and how.

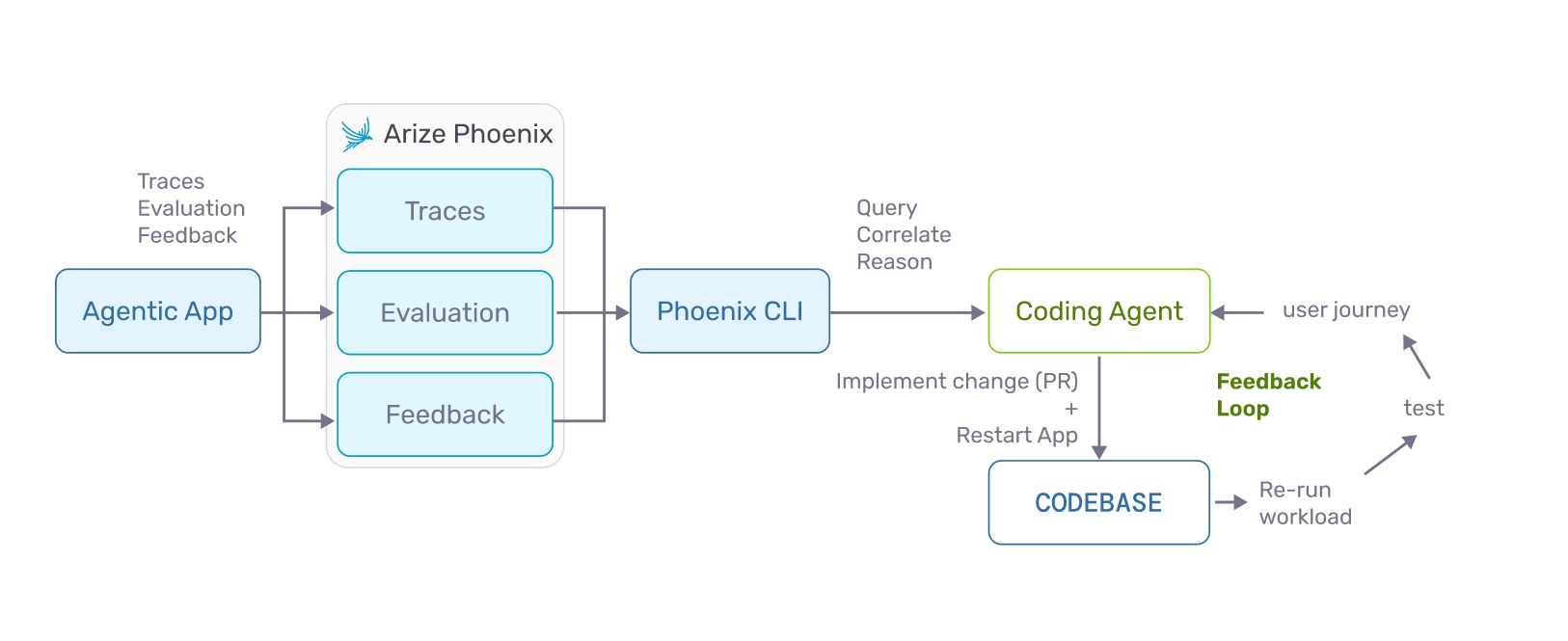

The second finding is that agents need their own observability stack. The team gave Codex access to telemetry through an observability environment. Agents could query traces via a query DSL. With that context available, prompts like “ensure service startup completes in under 800 milliseconds” or “no span in these four critical user journeys exceeds two seconds” became tractable. The agent could verify its own work against runtime evidence rather than guessing whether a change met the requirement.

From Dashboards to Programmatic Interfaces and Skills

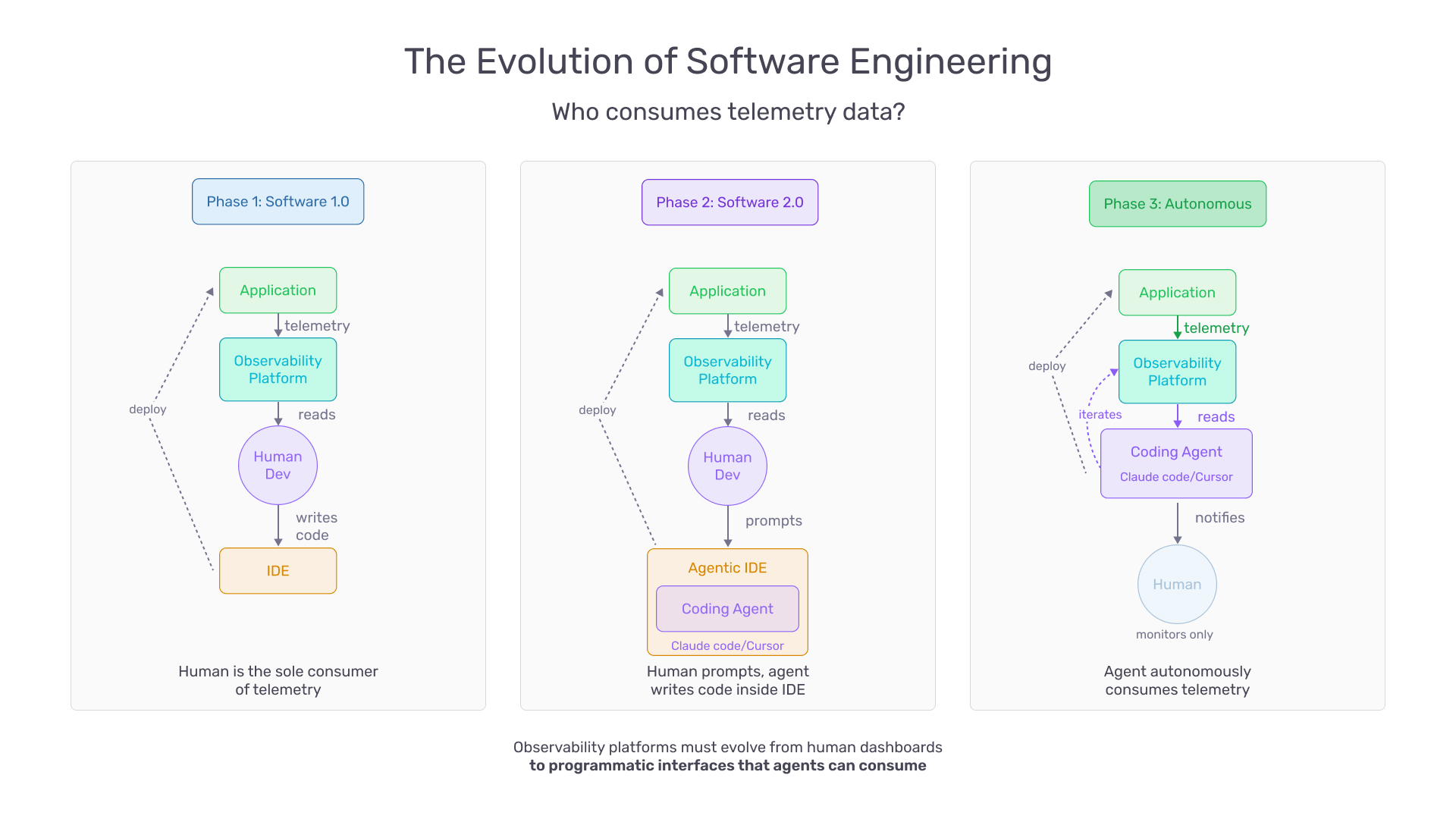

Historically, observability platforms have been built for humans — dashboards, visualizations, and interactive query builders designed for a person sitting in front of a screen.

This paradigm breaks down when the primary consumer of telemetry is an agent. Agents do not benefit from charts or heatmaps. They need structured data returned through APIs and command-line interfaces — data they can parse, filter, and reason over within their execution context. The underlying data is the same: traces, evaluations, feedback, and metrics. But the interface layer must evolve. Machine-readability, structured output, and composability become first-class design concerns.

Dashboards do not become irrelevant — humans still need visibility and audit capability. But the primary integration point shifts. Platforms like Arize Phoenix are beginning to ship developer-first tooling (including programmatic access patterns) that map naturally onto how agents operate. If you’re evaluating how to wire tracing into agent workflows, the Phoenix documentation is a good starting point.

The shift matters because access to tools is necessary but not sufficient. An agent with access to a tracing platform but no knowledge of how to use it effectively will produce noisy queries and draw poor conclusions. Skills — focused, composable units of methodology — transform a generic coding agent into one that follows the same diagnostic workflow an experienced developer would.

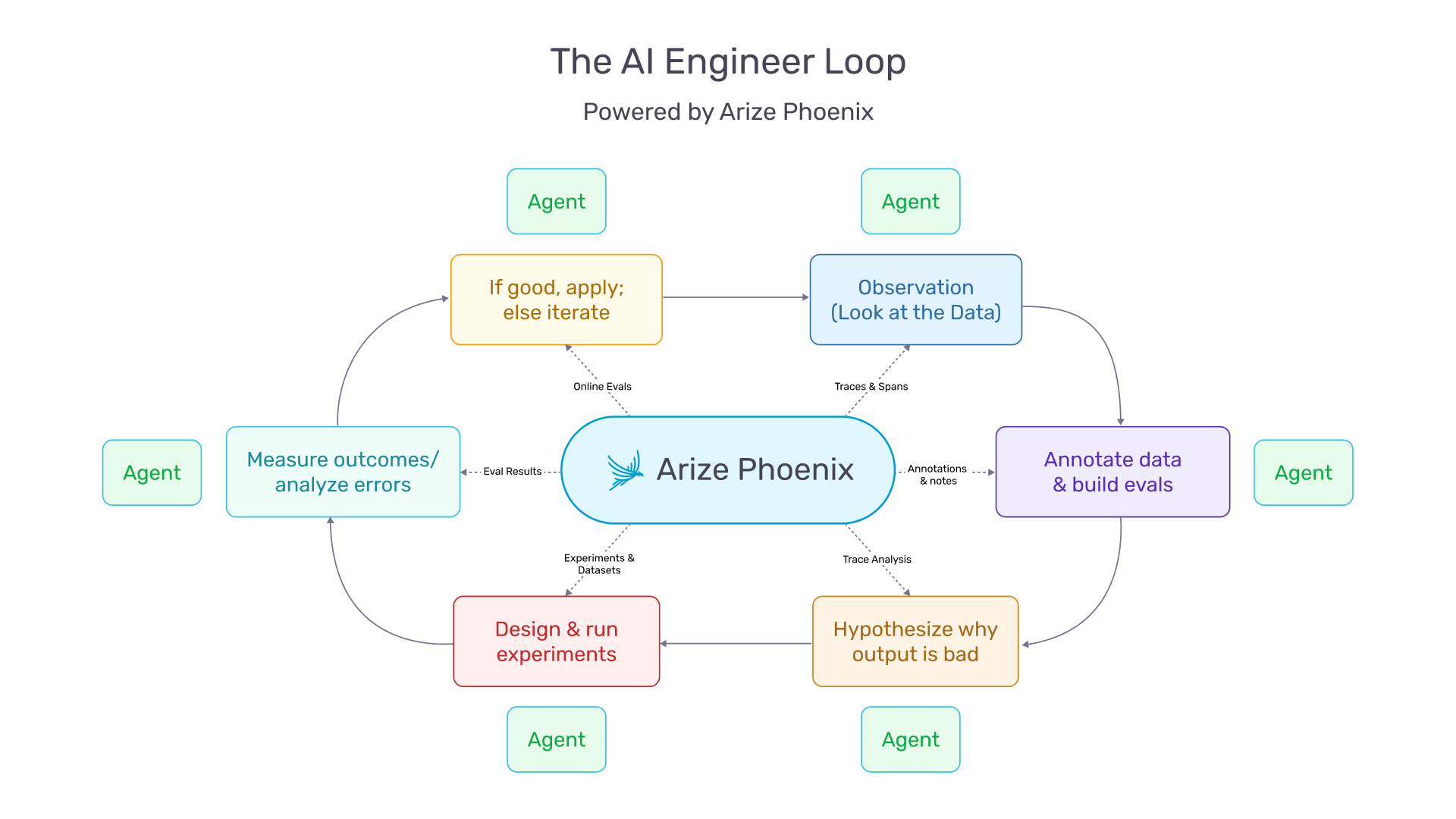

The Loop That Closes

These shifts describe a new development cycle. A coding agent receives a task. It instruments the relevant code paths, ensuring traces are captured. It executes its changes and collects runtime telemetry. It queries traces to verify behavior, identify regressions, and assess quality. It runs targeted evaluations. It iterates if necessary, using trace data and evaluation feedback to refine its approach. It submits the change with supporting evidence — traces, evaluation scores, and a summary of its reasoning.

This loop is only possible because traces serve as documentation for what the system actually does. Without telemetry, there is no source of truth. Without evaluations on real traces, there is no empirical basis for claiming a change is an improvement. The loop collapses into guesswork.

As agents approach full autonomy — as OpenAI’s harness engineering experience foreshadows — the human role transitions from reviewing every change to auditing the self-verification mechanisms themselves. Are traces captured correctly? Are evaluations meaningful? Are quality thresholds appropriate? The agentic engineer’s job is no longer to check the code. It is to check the system that checks the code.

What Comes Next

The transition to agentic engineering will not happen overnight or uniformly. But the direction is clear, and the lesson from every team that has pushed agents toward autonomy is the same: the critical work is never writing code. It is designing the environment, encoding constraints, structuring knowledge, and building feedback loops. As human involvement decreases, the systems that steer and verify agent behavior must become more robust, not less.

The organizations that invest early — giving agents access to telemetry, embedding evaluation into workflows, and exposing programmatic observability interfaces — will scale agent-driven development effectively. Those that do not will find their agents operating blind, producing code that looks correct but behaves unpredictably, and generating the very review overhead that automation was supposed to eliminate.

The tooling exists, in early form. The question is whether we treat coding agents as black-box code generators or as participants in the development process — equipped with the same signals, feedback loops, and verification mechanisms that have always been essential to building reliable software.

Arize note: If you want practical examples of wiring telemetry into coding-agent workflows, see Phoenix integrations for coding agents.