Co-Authored by Jason Lopatecki, Co-founder and CEO & Aparna Dhinakaran, Co-founder & Chief Product Officer & Laurie Voss, Head of Developer Relations & Aman Khan, Group Product Manager & Chris Cooning.

We’ve worked with thousands of customers building AI agents, and we’ve also spent the last two years building our own agent, Alyx, an in-product assistant for Arize AX. These experiences have given us some insights about how to build agents and in particular how agent memory works.

A lot of folks are writing about agent memory and we thought Letta’s brief take was particularly good, as well as insights from Vercel and LangChain. In this post, we aim to go deeper into the emerging best practices for agent memory design and how the lessons of the last 50 years of computing are still relevant.

The unreasonable effectiveness of Unix

We’ve seen incredible momentum toward files as the memory layer for agents, and this has accelerated significantly over the last year. But why use the file system, and why use Unix commands? What are the advantages these tools provide over alternatives like semantic search, databases, and simply very long context windows?

What a file system provides for an agent, along with tools to search and access it, is the ability to make a fixed context feel effectively infinite in size.

Bash commands are powerful for agents because they provide composable tools that can be piped together to accomplish surprisingly complex tasks. They also remove the need for tool definition JSON, since bash commands are already known to the LLM.

That is it.

Unix file system commands underpinning agent memory is nothing short of amazing … and kind of fun to see.

— Aparna Dhinakaran (@aparnadhinak) January 24, 2026

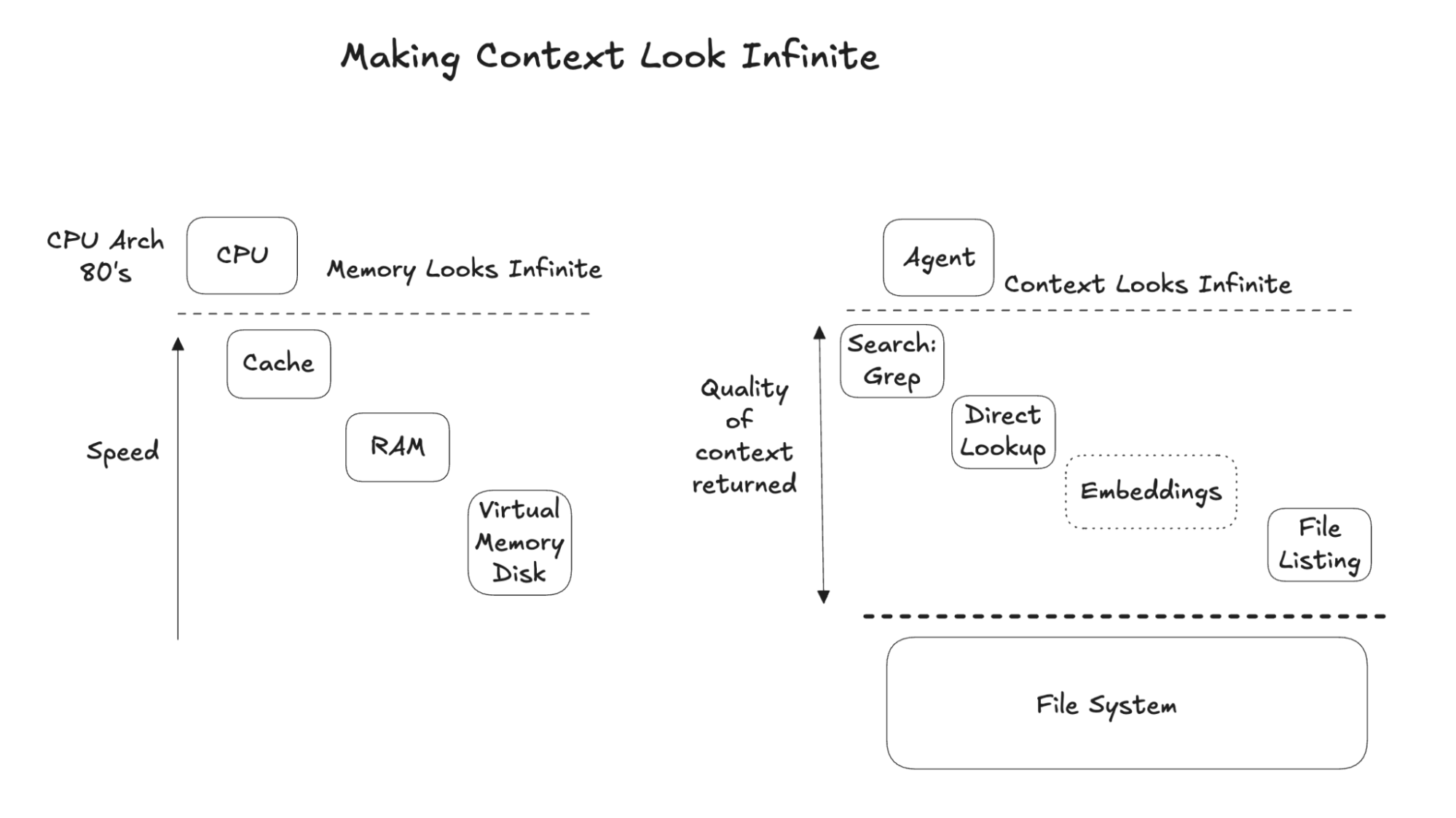

Lessons from the history of memory

The challenges in the 1980s of building CPU memory hierarchies, making memory appear both infinite and fast, have strong analogies to the current moment.

In the early days of CPUs, memory was small and everything outside the CPU was slow. Caching, RAM, and virtual memory created a hierarchy that balanced speed and size for programs. The Commodore 64 had 64 KB of memory and entire programs had to fit within that limit. The Intel 80486 later popularized on-chip caches in the late 1980s, making frequently accessed data appear fast, alongside virtual memory, which made memory appear effectively infinite. For agents, the file system acts as memory, and agent tools provide a dynamic tradeoff between infinite storage and returning usable context so the agent can continue acting.

What has been remarkable is that with a very small set of Unix command-line tools, particularly grep, ls and glob, we have unlocked a powerful form of agent memory.

Comparing with Cursor and Claude Code

The “filesystem plus Unix” approach has shown up clearly over the past year in the success of tools like Cursor and Claude Code, which operate over large amounts of data using simple Unix primitives. We were particularly intrigued by their use in Cursor and Claude Code, two of the leading agentic productivity tools on the market, and comparing them to what we’d built with Alyx.

| Tool | Task | Type | Agent Support |

| Search / grep -r / ripgrep | Find exact string or regex across the repo | Find File or Row Regex | Cursor / Claude Code / Alyx |

| ls | List files across the repo | Build Index | Cursor / Claude Code / Alyx |

| find | Finding files and directories | Find File or Row Regex | Cursor / Claude Code / Alyx |

| Semantic search | Embedding based search | Find File or Row Regex | Cursor (unverified) |

| Direct address lookup | Similar to RAM, take an ID and look it up | Find Row Direct Lookup | Alyx |

In all three assistants, these simple tools are used to greatly expand the available context window by rapidly searching, indexing and locating information within it.

everything is a file

this old unix idea works really well for ai agents. the agent already has read_file and write_file. long tool outputs just become files it can grep. too much stuff to track becomes a directory. it’s already a dynamic index

same tools, now used for dynamic… https://t.co/F5IL4TPuOq

— eric zakariasson (@ericzakariasson) January 7, 2026

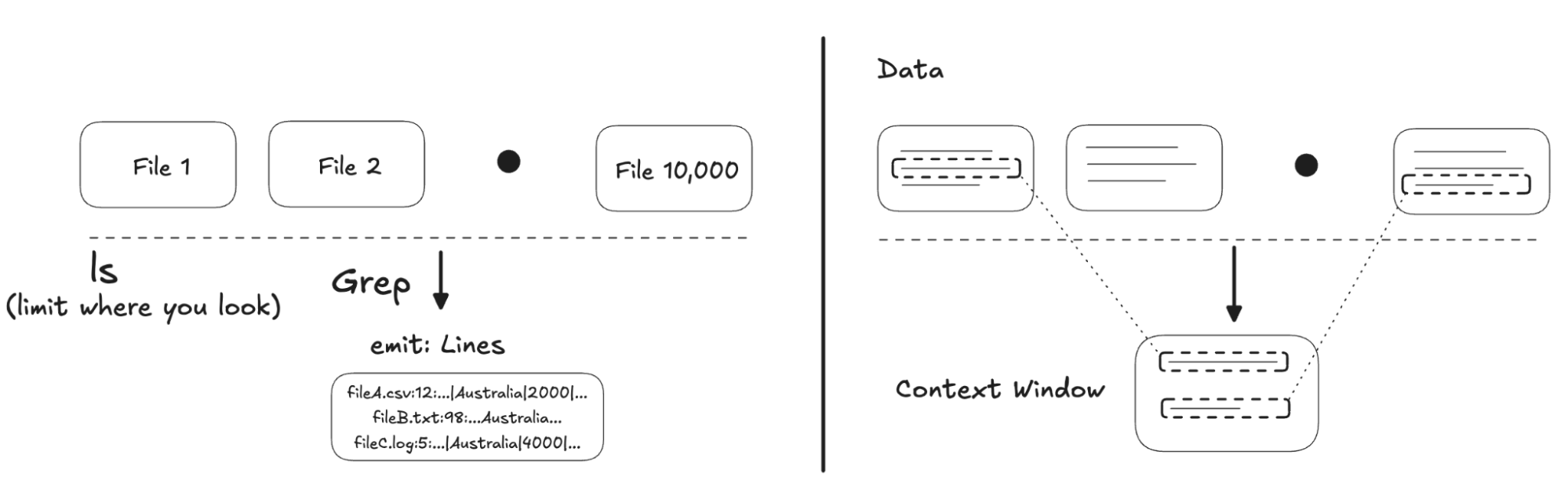

Evaluating agent approaches to large context problems

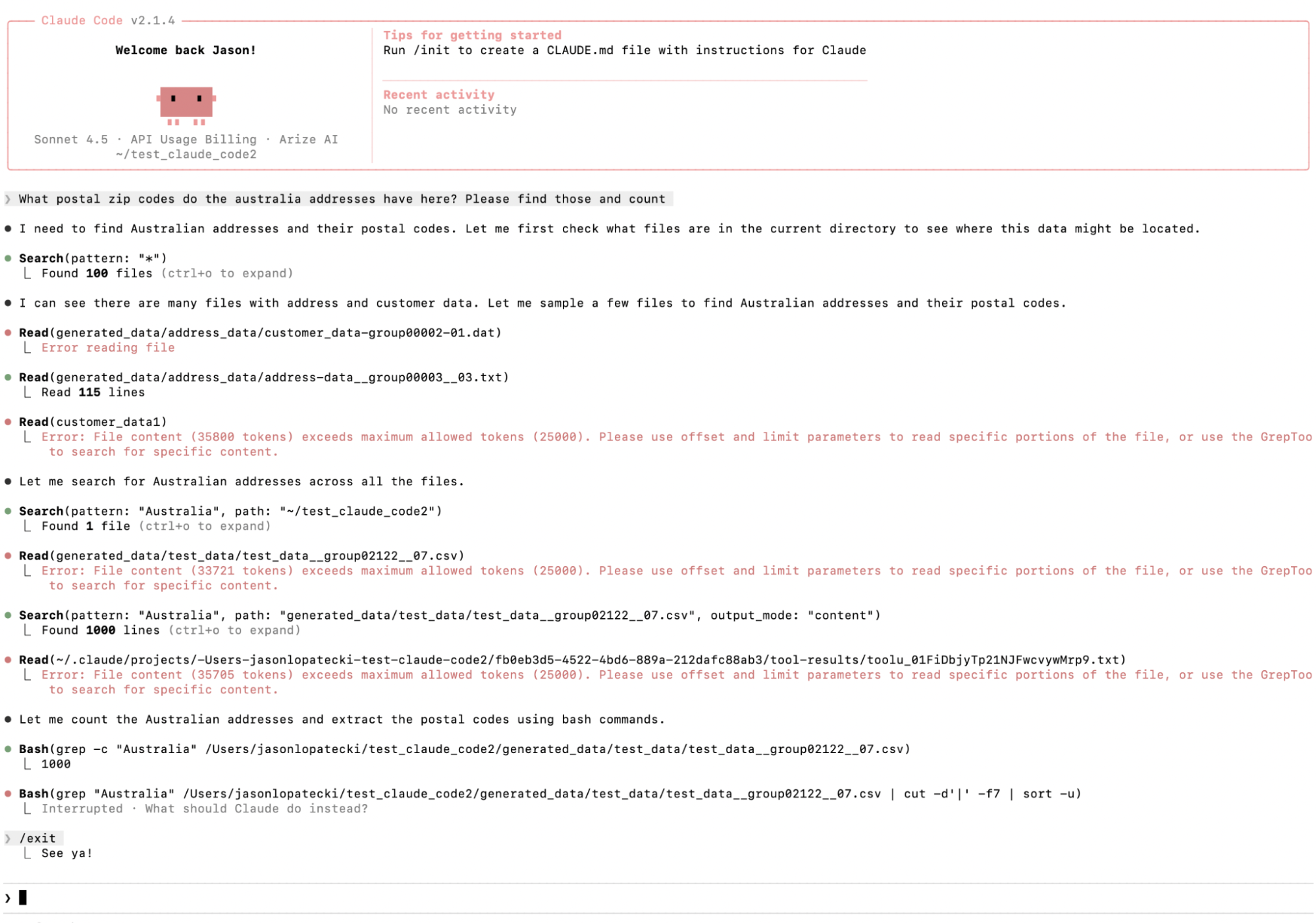

To look more closely at how popular agentic tools approach problems of large context, we built our own evaluation: given 10,000 files containing names and addresses, where only one file includes Australian addresses, find the Australian addresses and count them (the file is not named in a way that indicates it contains names or addresses or which kind). We have open-sourced a simple evaluation that was designed more to see how they work than truly judge results.

Input:

What postal zip codes do the Australian addresses have in the data? Please find those and count.

Expected output:

Unique postal codes: 3

- File 2000: 128 addresses (Sydney, NSW)

- File 3000: 134 addresses (Melbourne, VIC)

- File 4000: 738 addresses (Adelaide, Brisbane, Canberra, Darwin, Hobart, Perth)

Total Australian addresses: 1,000

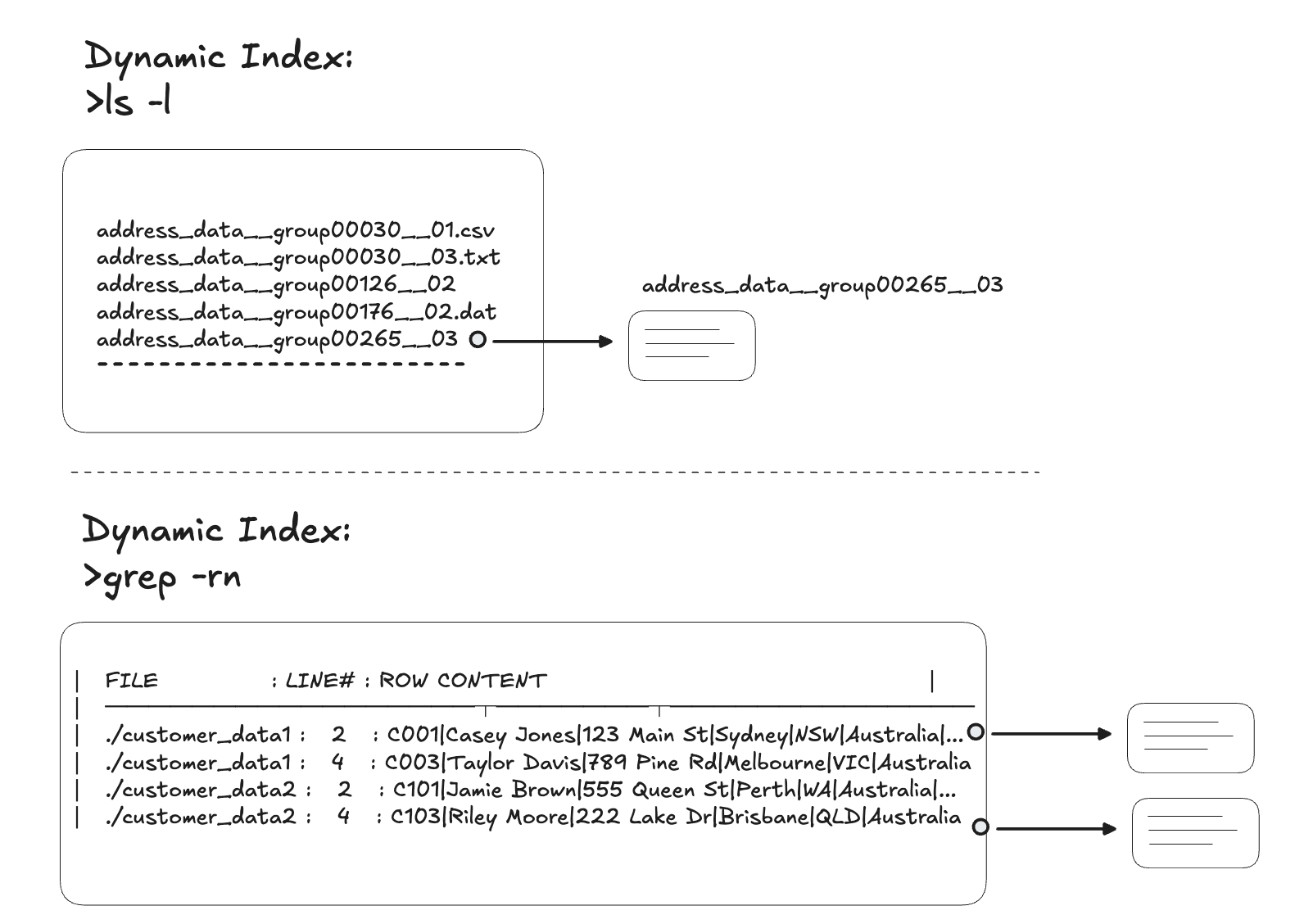

How Claude Code and Cursor solved the problem

Cursor and Claude Code both assembled a set of tools to search for and identify the relevant data, then placed that data into the context window to answer the question.

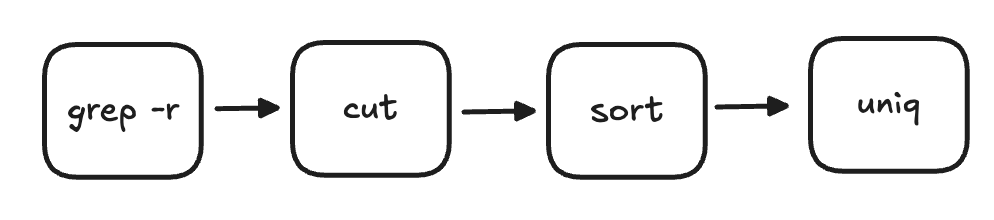

The tools grep, cut, sort and uniq were used to search across the data, narrow it down to the relevant rows, handle structured extraction, and finally use the resulting data in context.

Dynamic self-correction

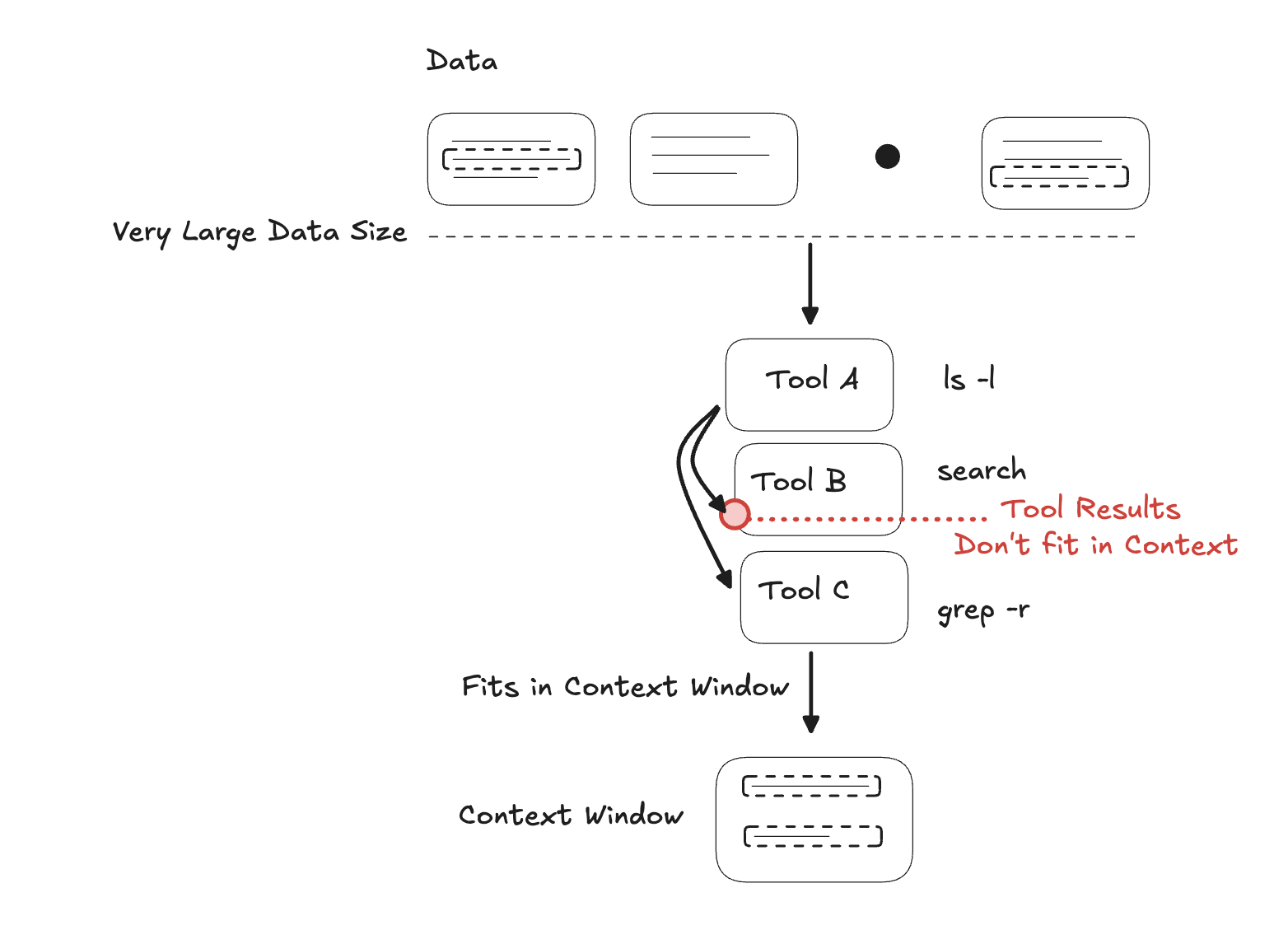

The executions were not flawless. Claude recognized that the data was too large for its context window and backtracked to an approach that would fit within the available context.

Internal context window management

The diagram above shows how Claude steps through tools, encounters a tool output that does not fit in the context window, then backs out and finds alternative tools to make the task work.

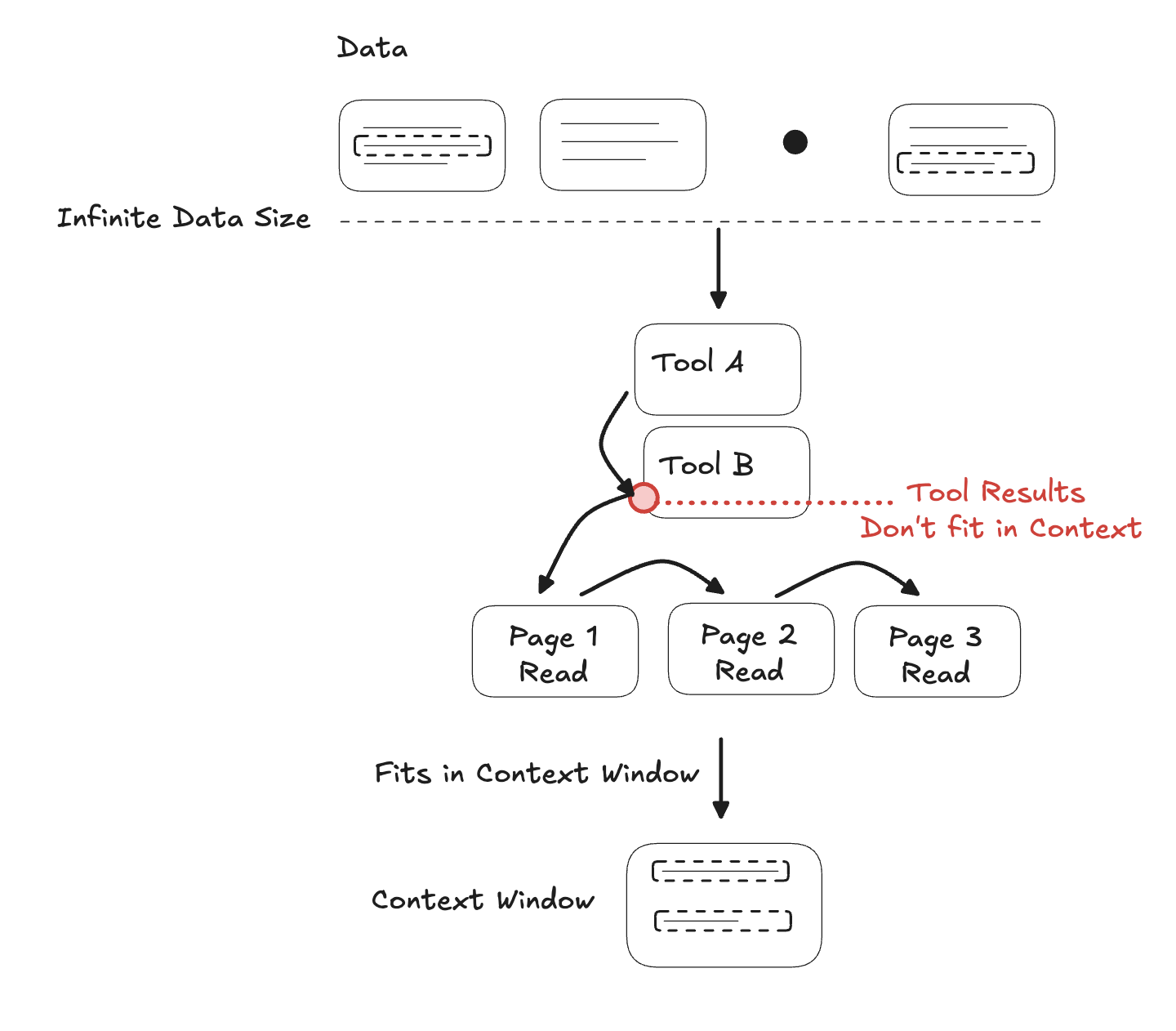

In addition to having multiple ways to bring data into context, giving agents tools to right-size data, such as paging through results, is a powerful technique. Cursor uses paging to step through results.

I see a lot of overwrought memory systems for agents.

Just use the file system instead.

Agents already know how to use it—you get grep, tail, ls, etc. for free. No complex embeddings needed.

— Thariq (@trq212) September 4, 2025

Composability is key

The reason Unix commands are so useful to agents is because they are composable. You can pipe the output of one command to the next.

The importance of composability of tools is something we arrived at over several generations of Alyx. Our original design relied on larger tools that performed many actions and returned complex results. In Alyx 2.0, every tool is designed with an explicit focus on how it can be combined with other tools and how data can be piped between them.

Emerging techniques: dynamic indexing and hierarchy

The Claude and Cursor results are examples of the emerging standard techniques in agentic context and memory management. They lean on the lessons of the past but the implementation is fundamentally brand new, and fascinatingly this approach emerges from the agents themselves rather than top-down design decisions. Let’s dig into the specific techniques and how they work.

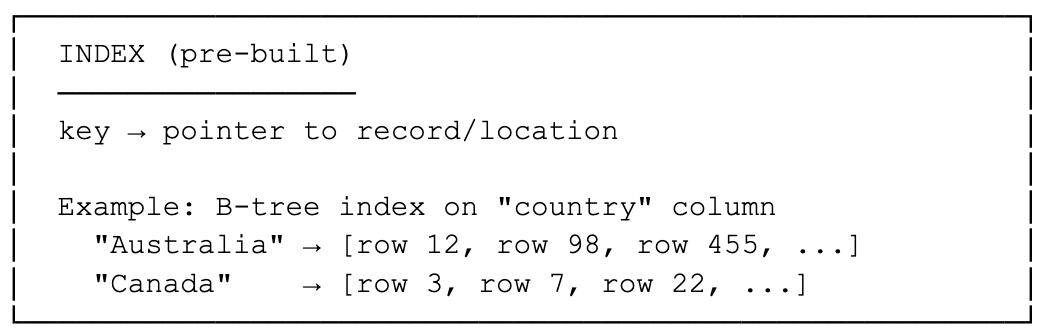

Dynamic indexes

In databases or search engines, an index is a pre-computed data structure that answers: “Given this key/query, where is the data?”

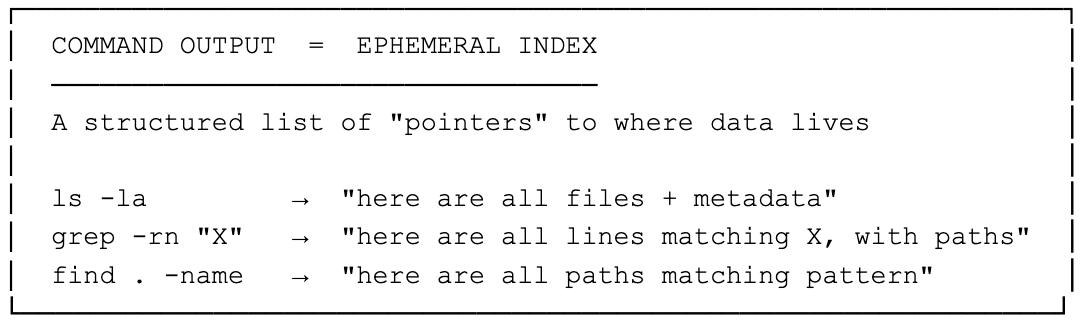

Unix commands as dynamic index generators

Commands like “ls”, “find”, “grep” don’t have a pre-built index. Instead, they scan at runtime and produce an output that functions like an index:

These outputs are not stored; they stream through stdout but they carry the same semantic role as an index: a map from query → locations. They differ from traditional indexes but have some surprising advantages:

| Property | Traditional Index | Dynamic (grep/ls) Index |

| Built when? | Ahead of time (insert/update) | On-demand at query time |

| Stored? | Yes (disk/memory) | No (ephemeral in pipe) |

| Cost | Storage + maintenance | CPU at query time |

| Flexibility | Fixed schema/keys | Any pattern, any field |

| Composability | Limited | Infinite (pipes!) |

Why this approach is so powerful

The Unix philosophy treats command output as a universal interchange format (lines of plain text). Each command’s output becomes the input (the “index”) for the next stage, letting you build ad-hoc query plans on the fly.

The agent uses Unix commands to build indexes in the context window. These indexes provide hints and pointers to the files or rows in the data that should be accessed. The result is flexible, fast, and powerful.

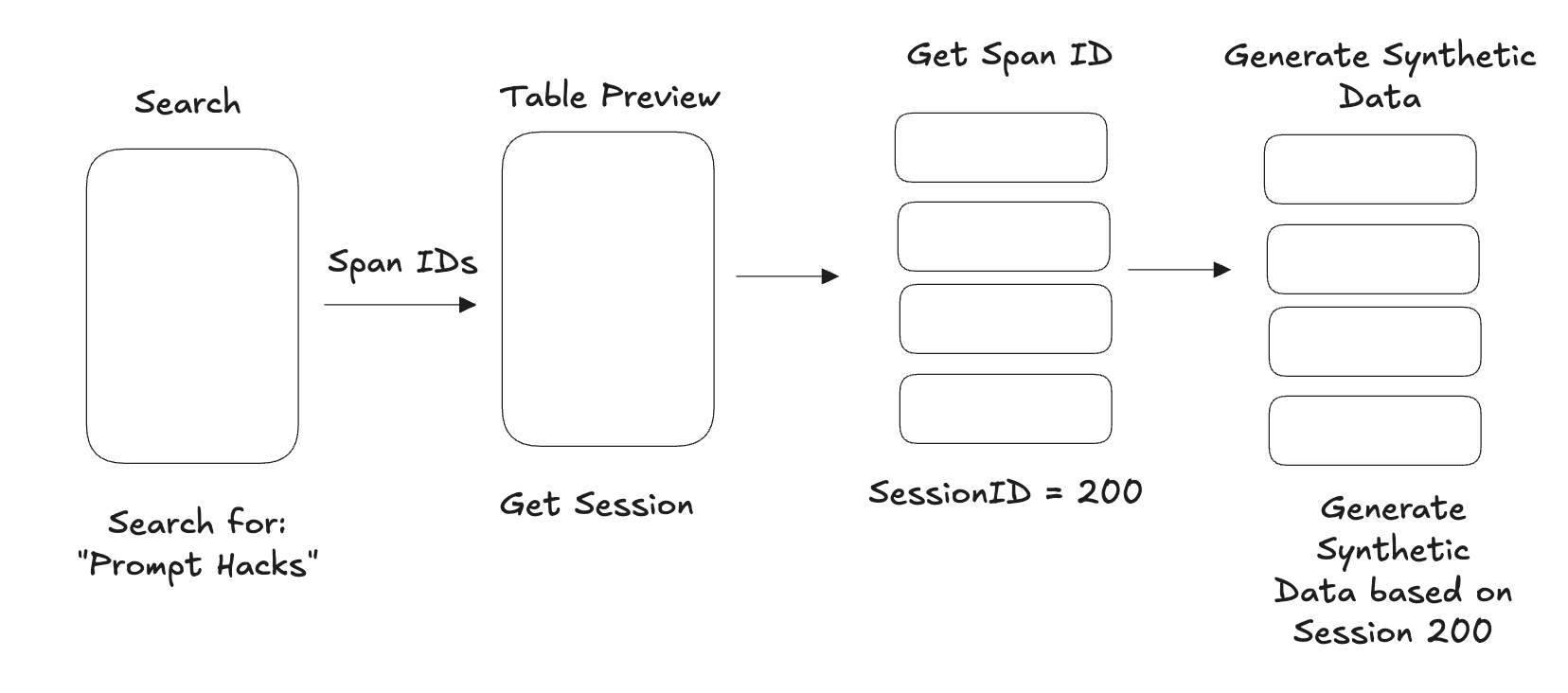

Dynamic Indexes with hierarchy in Alyx

As we mentioned, we go beyond what Claude and Cursor demonstrated in Alyx.

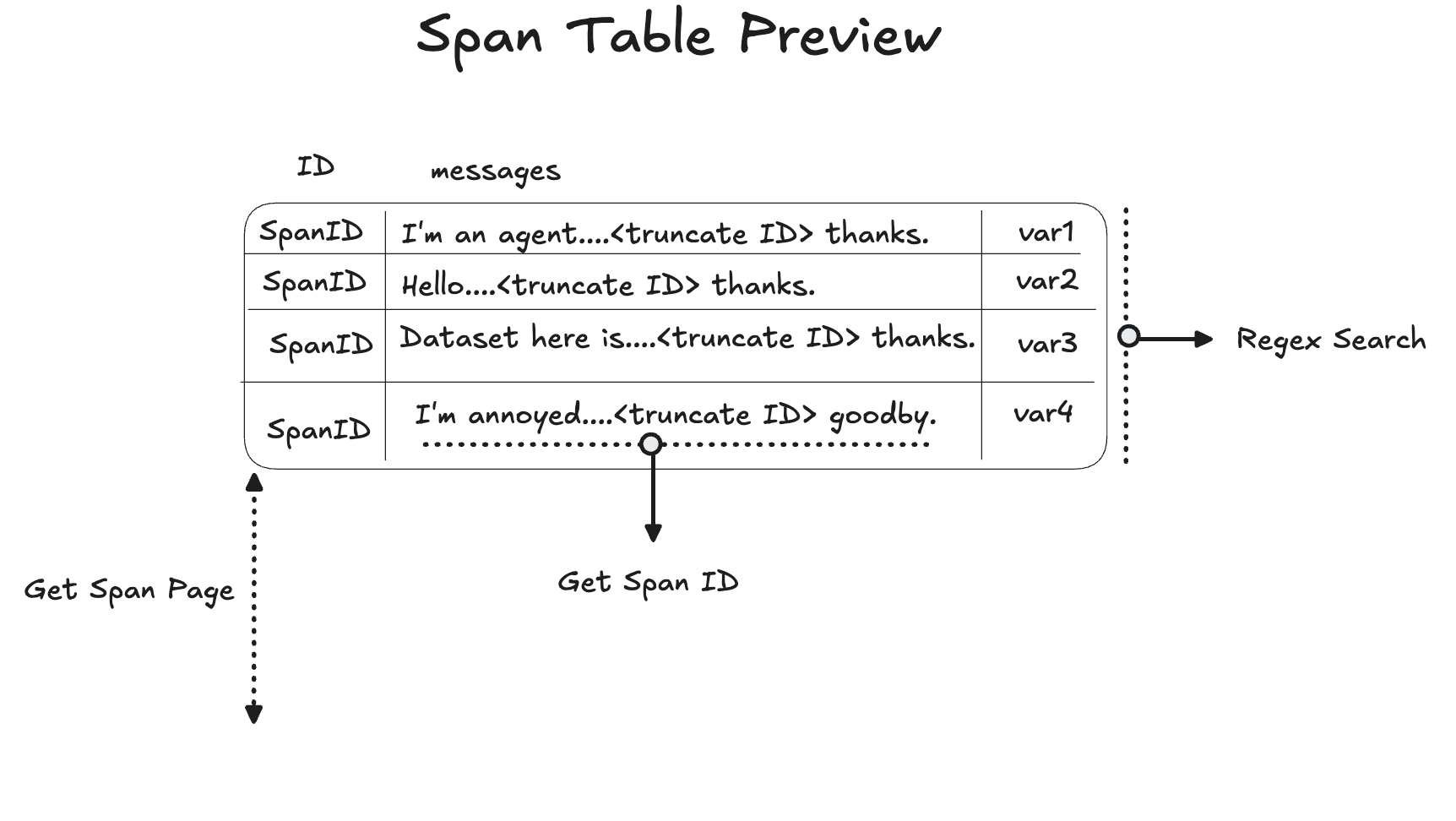

We also use dynamic indexes in Alyx, but in ways that differ from typical Unix command usage. In Alyx, we need to answer questions over large volumes of trace data, where a single row can sometimes be as large as the entire context window. To overcome this, we provide truncated sample data in a preview to the agent:

The span table preview can be thought of as an index. The truncated text in each cell gives the LLM a hint about the underlying context, and the span ID acts as a pointer to the full context.

We try not to drop any columns so Alyx can get a hint from every cell, and then look up span IDs as needed. We do drop rows to ensure everything fits within the context window, and Alyx can page in additional rows when required.

Alyx also provides tools to look up individual span IDs, similar to an address lookup, as well as tools to fetch additional pages of data. This follows the same general agent principles of using composable tools to access different levels of data fidelity.

The future of agent context management

As we look toward the future of agent context management, we see a few possible directions emerging.

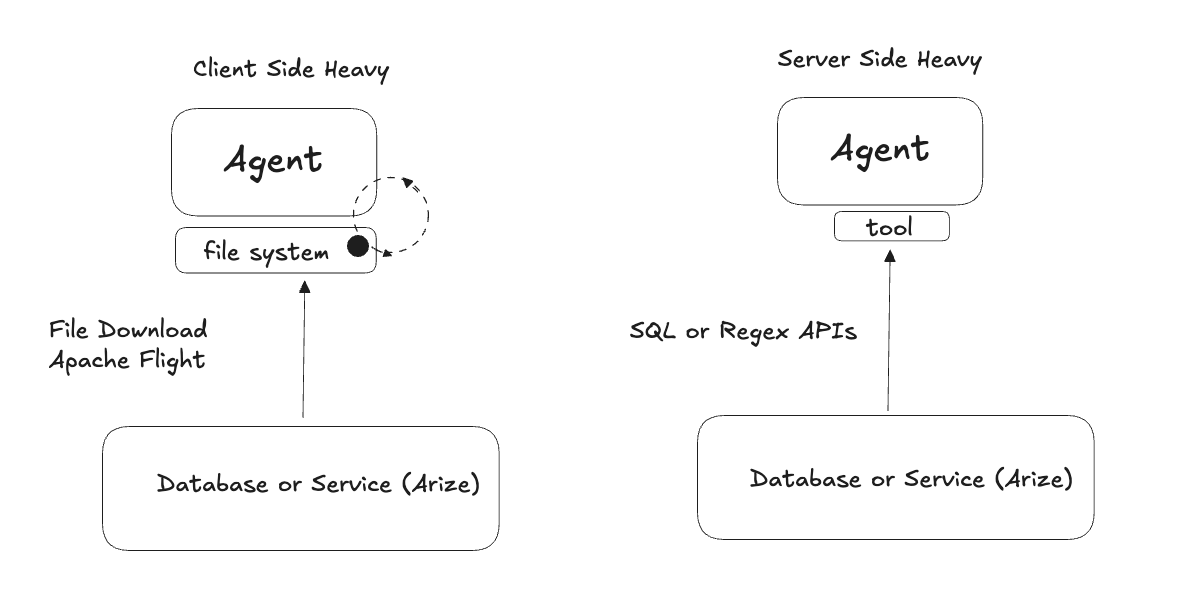

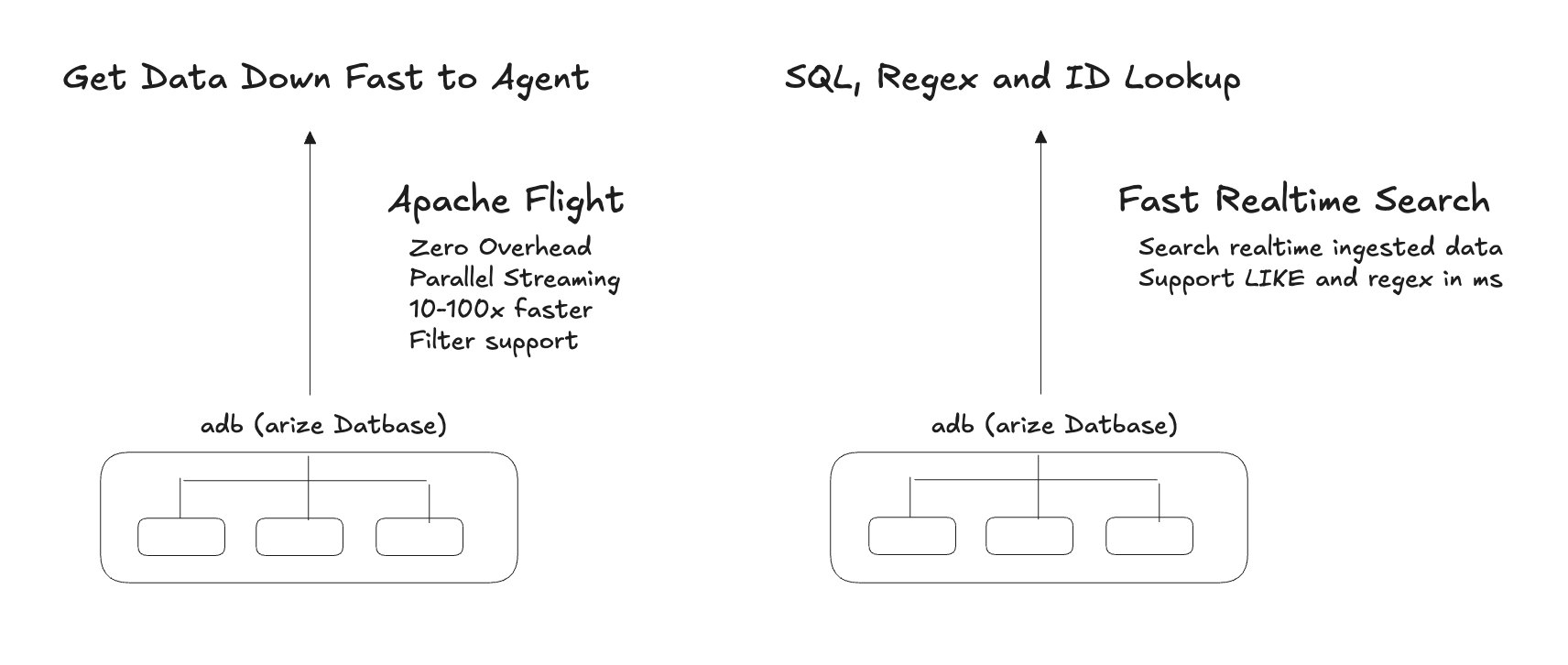

In Arize’s own observability industry, there is no realistic way to bring all data local, even on the file system: the data is simply too large. This leads to an important question: can you accomplish the same tasks with SQL that you can with Unix commands?

We believe that for complex operations the answer is no, but for simple retrieval operations you can write an evaluation that shows SQL performs better. For more complicated actions, such as data augmentation or using code-based tools, you want to fetch the data to the file system before taking action.

In our case, we designed ADB, the Arize database, to be both fast for real-time query APIs and fast for filter-based file downloads, so agents can choose the right tradeoff between remote querying and local execution as tasks become more complex. We think this pattern will define how agent memory systems are built going forward: a database provides one more step in the hierarchy of infinite context that we discussed right at the beginning.

Everything old is new again

The pattern is clear: the best agent memory systems aren’t built top-down: they emerge bottom-up from composable primitives. Whether it’s grep piping to sort, table previews pointing to full spans, or databases feeding file systems, the winning architecture is always a hierarchy of tools that agents can chain together. The Unix philosophy – small, focused tools that do one thing well and compose infinitely – turns out to be exactly what LLMs need to make 200k tokens feel like 200 trillion. Fifty years later, the lessons still hold: make memory feel infinite by making it hierarchical, and make it hierarchical by making it composable.