Embeddings: Meaning, Examples and How To Compute

To get started with monitoring image and language models, it’s important to start with the fundamentals. This section focuses on embeddings and their practical applications.

What Are Embeddings?

Embeddings are vector (mathematical) representations of data where linear distances capture structure in the original datasets.

This data could consist of words, in which case we call it a word embedding. But embeddings can also represent images, audio signals, and even large chunks of structured data.

Embeddings are everywhere in modern deep learning such as transformers, recommendation engines, SVD matrix decomposition, layers of deep neural networks, encoders and decoders.

Embeddings are foundational because:

- They provide a common mathematical representation of your data

- They compress your data

- They preserve relationships within your data

- They are the output of deep learning layers providing comprehensible linear views into complex non-linear relationships learned by models

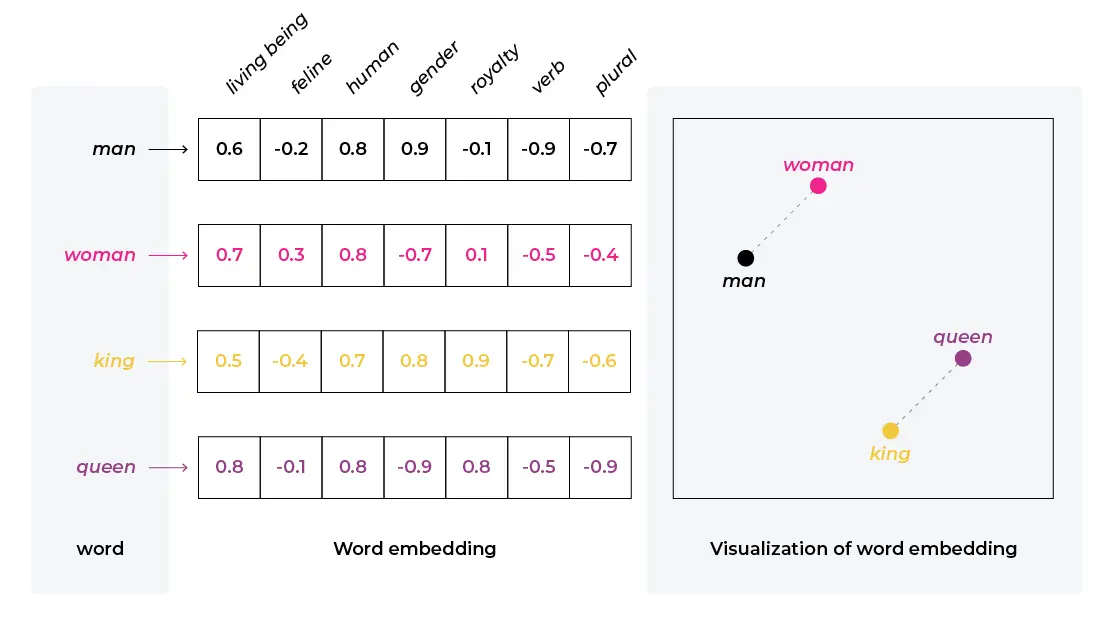

Word Embeddings: Example

Let’s look at a classic trivial example. If your dataset were just four words—queen, king, princess, and prince—you could use one hot encoding with a three-dimensional sparse vector. That means you would need three columns, which would contain mostly zeros.

| Word | Column_queen | Column_king | Column_princess |

| queen | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| king | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| princess | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| prince | 0 | 0 | 0 |

If you look at the words, however, they differ along two dimensions: age and gender. So you can represent the data as follows:

| Word | Column_female | Column_young |

| queen | 1 | 0 |

| king | 0 | 0 |

| princess | 1 | 1 |

| prince | 0 | 1 |

Not only did you get rid of one column, but also you preserved valuable information. Obviously in an example this simple, you do not gain much – but what if your corpus contained every word in the English language? What if it contained every word in every language? The latter representation would obviously be impossible to construct manually, but if it existed it would be very valuable. Hold on to that thought.

In practice, embeddings do not really give you ones and zeros but something in between, and they are much harder (if not impossible) to interpret on a column-by-column basis. Nevertheless, the important information can be preserved in this compact form.

Embeddings in the Real World

Recommendation Systems

One of the machine learning products that arguably drive the most commercial value today is recommender systems. From how to keep users engaged to what products to recommend to what news may be relevant to you, recommender systems are ubiquitous. One common approach to a recommender system is (e.g. what do people with tastes similar to yours like?). Collaborative filtering in modern recommender systems almost always uses embeddings. As a result, many data scientists’ first introduction to embeddings is in recommendation systems.

A number of years ago, embeddings also started showing up in other types of commercial models, such as the original word-to-vec. The way embeddings were generated in word-to-vec was noticeably different from the matrix factorization approaches used in recommendation systems; they were based on training word relationships into linear vectors. Word-to-vec spurned on many teams to determine how far the relationships could go beyond words, and what relationships could be represented by the embeddings. Fast forward to the present day and transformers – the magic behind many modern AI feats of wizardry – can be viewed as a complex hierarchy of probability-adjusted embeddings.

In short, embeddings are everywhere in modern AI. In addition to being ubiquitous, the representation of data as an embedding has another advantage: it can serve as an interface between models, teams, or even organizations.

Here are a few other examples of how embeddings might be used in the real world.

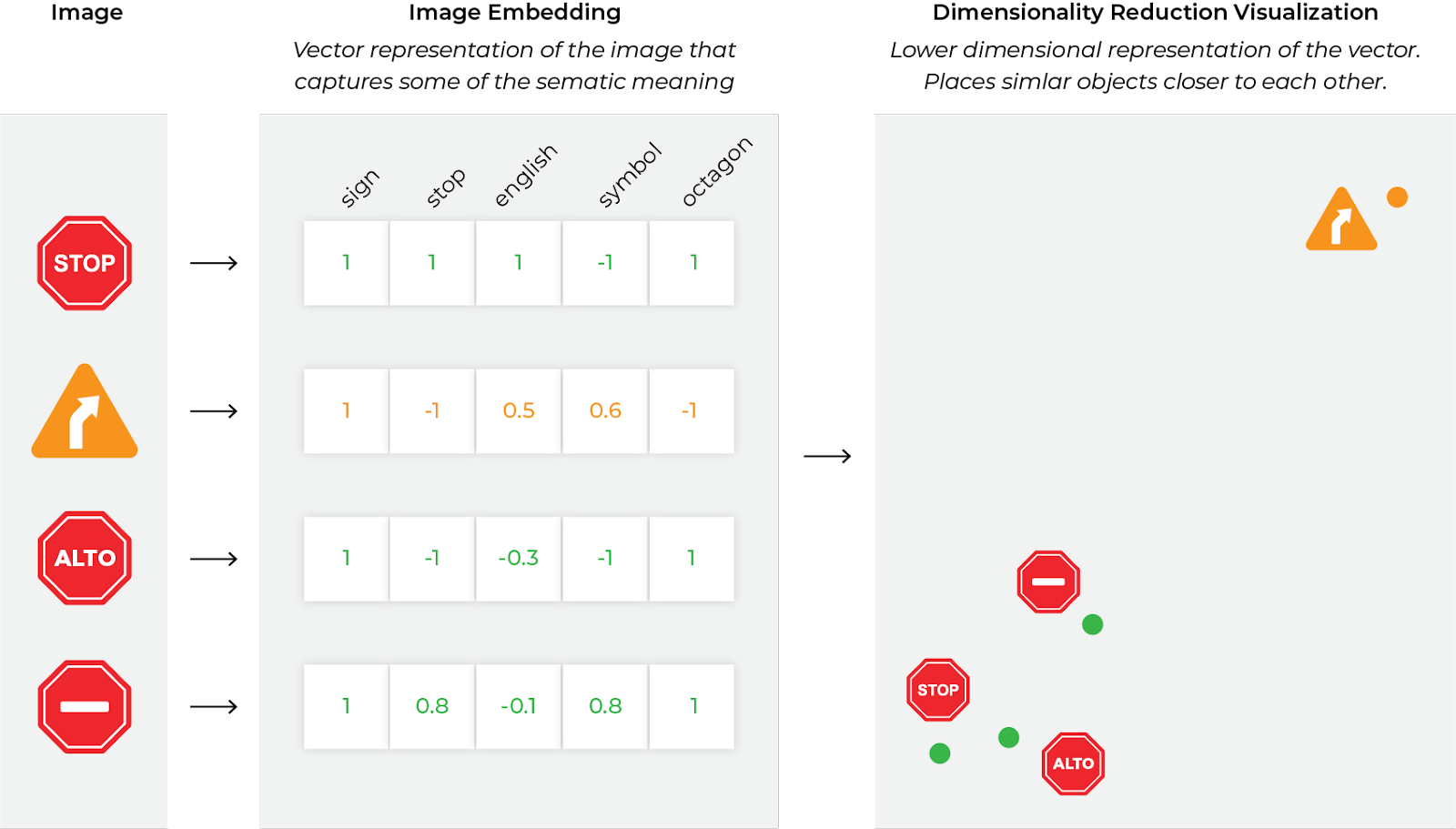

Self-Driving Cars

Another important and challenging problem where embeddings are used is self-driving cars. Say your team is training the model that feeds into the car’s braking system. One important model feature you want to have is “stop sign.” With this in mind, you train on a bunch of stop signs in your area, but unfortunately in the real world you may encounter a stop sign in a different language or even a different shape. It would be nice not to worry about that. Luckily, another team at your company has a stop sign embedding for you to use.

Now you can focus on one part of the problem and the other team can be responsible for traffic sign embedding and serve it to you as an input. Embeddings become the interface between models, just like a REST interface between different microservices. You may need to agree on dimensionality, but beyond that the downstream model can be a black box.

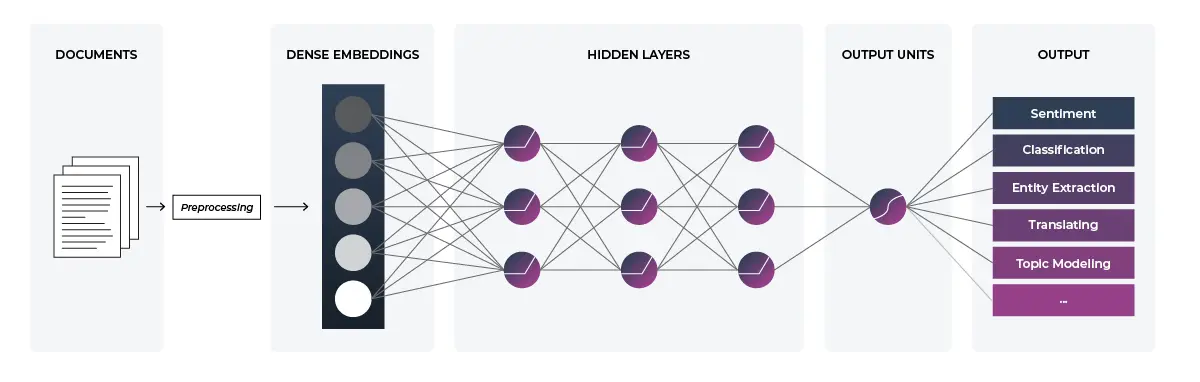

Document Classification

If you spend any time paying attention to recent developments in machine learning, many of them revolve around natural language processing. These tasks can include translation, sentiment analysis, topic modeling, summarization and much more. At the core of the recent explosion in the field is a particular type of neural network called a transformer. Today’s transformers use embeddings in multiple places throughout the architecture, including input and output. As far as mathematical data go, language is extremely unstructured and therefore presents a perfect opportunity for embeddings to shine. Even much simpler architectures (like the one pictured) rely on embeddings to represent the input data.

Since embeddings by definition represent data more compactly, they can also be used for compression purposes. ImageNet, for example, is 150GB. If embeddings can help you represent it in 1/50th of the space, that makes a lot of your tasks simpler.

The core value of embeddings is that linear relationships such as distance, projections, averages, addition and subtraction all have meaning in the vector space. Very simple linear manipulations can provide a lot of value. A dot product can tell you how similar two items are to each other. An average of different cities can create a representative vector for an average “city.” Projections can show how one concept is related to another.

How Do You Compute Embeddings?

Much of the discussion about how to create an embedding today revolves around deep neural networks (DNN). Since DNN-trained embeddings are so prevalent in the industry, this post will mainly focus on them. However, it is important to point out that you do not need a DNN to produce an embedding. GloVe, for example, is a very important word embedding that does not use DNNs.

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are common ways to obtain embeddings that do not rely on neural networks. Both come from the family of dimensionality reduction and matrix factorization techniques and can operate efficiently on huge amounts of data.

There are many ways you can extract embedding vectors from a DNN model, given that there are many model architectures applied to different use cases. Let’s look at one approach.

Say you are looking for a word embedding to use for a translation system. That’s a pretty natural application for the technology since the similarity between “cat” in English and “gato” in Spanish, for example, are likely to be preserved. You can train a transformer model on a large corpus of text in multiple languages.

The architecture can be very complex or very simple, but let’s assume an input layer (encoder), many hidden layers in feed-forward fashion, and an output layer (decoder). Ignoring for a second the positional attention of a transformer, when your network sees “cat” in a certain word position it has one set of activation values on the associated hidden layer – and when it sees “dog” it has another. Great! That’s your embedding. You can simply take the activation values at that layer.

This is of course just one way to represent a cat. Others may include:

- Taking an average of activation values across the last N layers

- Taking an average of Embeddings at word positions to create a context

- Taking an embedding from the encoder vs decoder

- Taking only the first layer values

Model architecture and your choice of method will affect the model dimensionality (how many values a vector has) as well as hierarchical information. Since the dimensionality is up to you as a machine learning practitioner, you may be wondering: how many dimensions should an embedding have?

Sometimes the model and architecture is already set in stone and all you are doing is extracting an embedding layer to understand the internals. In that case, your dimensions are laid out for you. However, there is a big design tradeoff if you are building the model itself to generate an embedding.

Fewer parameters make the embedding much simpler to work with and much more useful downstream, but having too few parameters may miss important information worth preserving. On the other hand, an embedding the size of the original data is not an embedding! You lose some compression benefit with each dimension you choose to keep.

One other benefit in keeping the embeddings larger: the larger the size of your embedding, the simpler distance metric that you can use. More complex distance metrics are often hard to describe and hard to understand. This is one of the major reasons that embeddings typically use a few hundred to a few thousand parameters.

Conclusion

Embeddings are dense, low-dimensional representations of high-dimensional data. They are an extremely powerful tool for input data representation, compression, and cross-team collaboration.

While there are many ways to obtain such representations, as an engineer you must be mindful of size, accuracy, and usability of the representation you produce. This, like so many other undertakings in machine learning, is an iterative problem, and proper versioning is both challenging and essential.

Though embeddings greatly reduce the input feature dimensionality, they are still difficult to comprehend without further dimensionality reduction through techniques like UMAP.